“I will make the case that much of what passes for normal in our society is neither healthy nor natural, and that to meet modern society’s criteria for normality is, in many ways, to conform to requirements that are profoundly abnormal in regard to our Nature-given needs—which is to say, unhealthy and harmful on the physiological, mental, and even spiritual levels.” – Gabor Maté, The Myth of Normal

It is refreshing to see the rise of Dr. Gabor Maté. The 79-year-old physician who lived through the Holocaust is precisely the sagacious voice to be leading us into a new collective paradigm that embraces Maté’s interpretation and expansion of the biopsychosocial model that embraces the work of many great theorists before him.

Maté’s first-hand experience with a trauma-filled life and later quest to treat it has led him to become a prolific voice for advancement and change around the way we view trauma and its affects in a modern society — one that does not often allow a space for such reflection, or much reflection at all.

“Trauma is that scarring that makes you less flexible, more rigid, less feeling and more defended.” – Gabor Maté

With his works and talks shared on a number of platforms on a daily basis, Maté has achieved a position in which he can — and I think is — bringing enhanced consciousness and awareness on a multitude of key subjects including and beyond the implications of trauma (which itself is significant enough).

Spirituality, Gabor Maté & The Biopsychosocial Model

The biopsychosocial concept focused on and expanded by Maté in his work will not be new to many engaged in mind-body research and spirituality but through its nomenclature — it is the model that looks to the connection between biology, psychology, and socio-environmental factors in the health and life function of an individual.

The idea of ‘mind, body, spirit’ that has been embraced by the spiritual community for untold time comes through Maté’s biopsychosocial approach in a meaningful way, I believe.

“The biopsychosocial approach systematically considers biological, psychological, and social factors and their complex interactions in understanding health, illness, and health care delivery.” – University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry

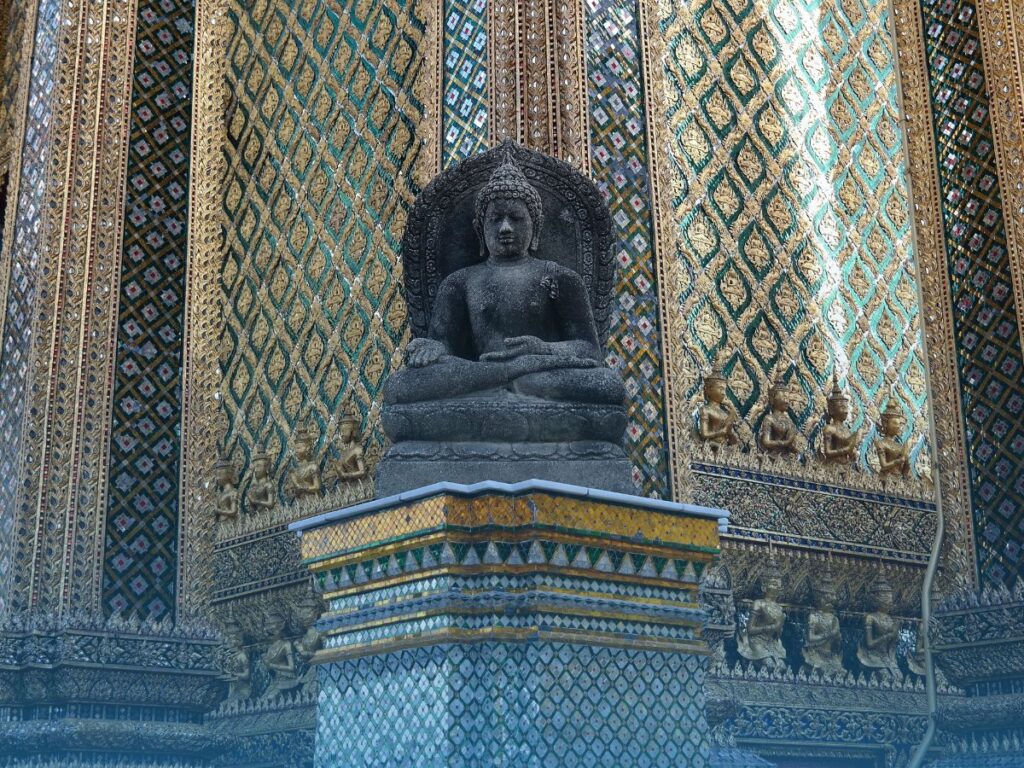

Many who have engaged in spiritual discovery and are familiar with many of the great works within various spiritual traditions may consider Maté’s interpretation of the biopsychosocial model to harbor a modern appreciation of such wisdom. The Tao was written around 400 BC, and the Upanishads between 800 and 500 BC. Countless other ancient texts should of course also be considered, as well as verbal traditions passed down such as in the Native American First Nations understandings that were are still rarely documented outside of works like Black Elk Speaks. Among the many traditions, the theme of oneness amid the perception of differences, mind-body-spirit, shines through.

The ancient Greeks held the connection between mind and body to be of significant importance. The very word ‘psyche’ comes from the Greek work psykhe, meaning “the soul, mind, spirit, or invisible animating entity which occupies the physical body.”

Ken Wilber’s work on holons, as discussed in his book his Sex, Ecology, Spirituality also presented a holistic model of interconnectedness through his integral theory that incorporates ancient understandings with modern knowledge and specificity:

“Every holon is not only a whole, it is also a part. And as a part, it has value for others—it is part of a whole upon which other holons depend for their existence.” – Ken Wilber

The Ever-Shifting & Often Damaging Concept of ‘Normal’

“I think normalcy is a myth. The idea that some people have pathology and the rest of us are normal is crude. There’s nothing about any mentally ill person—and it doesn’t matter what their diagnosis is—that I couldn’t recognize in myself.” – Dr. Gabor Maté

It is important consider that the concept of what makes something ‘normal’ in the first place is always shifting as the collective develops and changes. There are endless examples of this, including many ‘normal’ behaviors and practices now understood to be tragic and unthinkable (horrific treatment of certain groups of people, punishments for various ‘crimes’ now considered normal behavior, etc.).

As the collective increases in consciousness and scope, it reflects back upon its previous systems and cannot fathom what once was; this is more of Ken Wilber’s work on the evolution of holons.

But let’s take a more casual approach and just consider the shifts of normalcy in the way that humans present themselves in fashion trends and appearance.

In early Tudor England, Elizabeth I’s sweet tooth and subsequent sugar intake evidently caused her teeth to decay and ‘turn black’, sparking a trend in which English women purposefully blackened their teeth as a statement to show they had enough money to purchase sugar for themselves.

For quite some time, it was normal for men to wear powdered wigs as a means of accepted dress (think George Washington) – of course one reason for this was to mask their smell with highly-scented wigs. In the 1700s, the upper class rarely – if ever – bathed, as was considered normal.

Maté’s work is indeed more focused on impactful considerations such as trauma, and the stigmatization of all non-normal cognitive aspects, but the application of ‘normal’ remains ever-changing all the same. What was once considered ‘crazy’ even in the last 100 years has changed dramatically.

Imagine all of the stress, shame, pain, and altered life paths that have transpired as a result of trying to fit in with a ‘norm’ of the past that we would now laugh off? Something that will seem so fleeting once more in the future we surely remain locked into to this day, living up to or comparing ourselves against the the standards of ‘normalcy’ (often unrealistic and quite far from the average or completely distorted) in beauty, success, relationships, societal expectations, social situations, and so on.

As we enter a world that looks at considerations such as neurodivergence in the discussions of the mainstream, the shift is in towards a more advanced reconstruction of ‘normalcy’ and its implications. When we recognize that 1 in 5 people in the United States are reported to have a mental illness, 90% percent of people don’t like their job, 51% of Americans saying they feel hopeless or depressed, 1 in 5 adults feel shame over their body image, and nearly 20% of people say they would trade ‘years of their lives’ for the ‘ideal’ body, it seems clear that the ‘normal’ we are striving towards is much more a fractured and distorted ideal than a reality.

Instead, we might find a more cohesive connectedness in striving away from the idealized ‘normalcy’ that sets our minds up against an illusionary and misguided target of being or beating ‘normal’; Maté is correct, the statistically-supported ‘average’ is far different than the mythological normalcy we have subscribed to — and perhaps through recognition of this, we can find a greater connectedness as unique human beings no longer challenging our value against an ever-changing target of normalcy.

It’s time to give up the myth of normal.